A big fear during the government shutdown was that the data blackout might be cloaking fundamental shifts in the economy even as it kept policymakers mostly in the dark and, hence, wary of responding inappropriately. Amid that proverbial fear of the unknown, the Fed understandably chose to mitigate the bigger risk, taking out preventive rate cuts as insurance against a weakening job market. Implied in that decision, the Fed believes its policy tools are better equipped to stop an inflation flare-up than arrest a deteriorating job market.

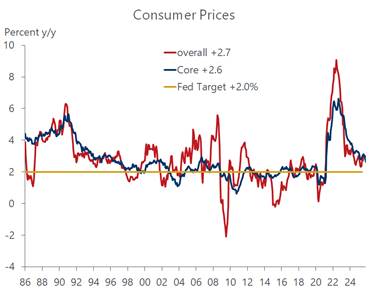

Indeed, at the time of the first of three consecutive rate cuts, there was more evidence of weakening labor conditions than of a sustained increase in inflationary pressures. While the inflationary implications of tariffs still grabbed headlines, the Fed – as well as most economists – believed they would lead to a one-time boost in prices, not a durable increase in inflation. Now that the data spigot has reopened, it looks like the fear of operating in a fog was overblown. Whether the Fed’s actions were too much or too little (as the White House claims) little damage was done.

True, the shutdown caused some pain, particularly for households deprived of federal benefits {such as SNAP) and government workers who missed paychecks. Importantly, the episode amplified the bifurcation that underpinned economic activity prior to the shutdown. Even as the lost income and government benefits mostly punished lower- and -middle income households, the continued advance in stock prices burnished the net worth of wealthier individuals, whose spending kept the growth engine humming through the balance of the year. The final months no doubt suffered a modest growth hit, but the setback directly linked to the shutdown should be more than made up in the current quarter as lost paychecks and benefits are restored.

It will be a while before economists can fully quantify the direct impact the shutdown had on the economy. After all, data for the period is still coming in, and much of it is flawed due to impaired data collection process. What’s more, separating the shutdown from the myriad other influences buffeting the economy is a difficult task. That said, a $30 trillion economic juggernaut is not easily knocked off the rails, and by all accounts its hallmark resilience was very much in evidence in the fourth quarter. For one, the shutdown sapped little joy from the holiday shopping season. Retail sales in November notched a solid 0.6 percent gain, matching the strongest increase since June and rebounding convincingly from the 0.1 pullback in October.

The wide swing reflects the heavy influence of volatile auto sales, which were depressed in October by the expiration of the tax credit on electric vehicle purchases. But even without that influence, the resilience of consumers came through loud and clear. Excluding autos, sales rose a solid 0.5 percent, more than double the October increase. Notably, the November increase in retail sales, both with and without auto sales, was twice as strong as the average increase over the previous 12 months, and that includes the front-loading of purchases in the months before announced tariffs kicked in. More impressive is that sales in November were as broad based as it was formidable. The only major category that saw a decline was in furniture and home furnishings, reflecting a moribund year for home sales.

Barring a collapse in December, the economy’s main growth driver should make another solid contribution to the fourth quarter’s performance. According to real time reports from banks and other trackers of consumer spending, households kept their wallets open last month, dipping into savings and using credit cards to finance purchases. And with stocks notching another month of gains to end the year, the wealth effect continued to support discretionary spending. According to the Airlines Reporting Corporation (ARC), domestic airlines booked 20.4 million passenger trips in December, 7 percent more than a year ago. The good news is that the average ticket price fell 2 percent in December from the previous month.

That, in turn, is a snapshot of improved purchasing power that kept consumers in a buying mood last year. Wage growth slowed along with jobs, but so too did inflation notwithstanding the tariff-induced price bump, most of which was absorbed by businesses. For sure, the much-ballyhooed lagged effect of tariff passthroughs did not show up in the closing months of the year, as the December increase in the consumer price Index held steady and its core component that strips out volatile food and energy prices came in a touch weaker than expected. Recent months’ data of course needs to be taken with a grain of salt, as the government shutdown disrupted data collection and made monthly comparisons difficult to interpret. But year-over-year comparisons provide a more representative gauge of the inflation trend, and the direction pointed more down than up towards the end of 2025. The overall CPI, at 2.7 percent, closed out the year 0.2 percent lower than the year before, and the slowdown in the core CPI was even more impressive, ending the year up 2.6 percent versus 3.2 percent in 2024.

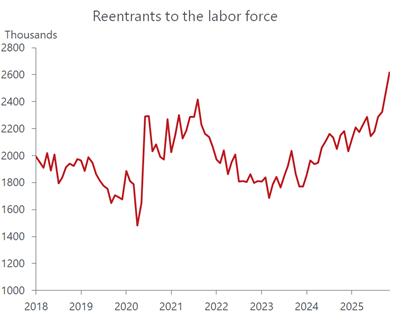

The slower pace of price gains over the course of the year enabled workers to stay ahead of inflation, as average hourly earnings increased 1 percent faster than consumer prices. On the surface, that’s a decent cushion but it was less so for the 80 percent of nonmanagement workers whose wage gains slowed much more sharply than for the overall workforce. At the start of the year, this group’s average hourly earnings stood slightly over 4 percent higher than a year earlier, but the wage gain shriveled to 3.55 percent at year’s end. For all workers, the slowdown was more muted, from just under 4 percent to 3.75 percent. Importantly, the biggest drop in wage gains for nonmanagement workers occurred late in the year, which aligns with recent Labor Department data showing sizeable increases in unemployment for younger and minority workers.

The disparity in wage and employment growth among lower and higher earning workers echoes the bifurcated underpinnings of the economy’s performance last year. The late-year trend augurs for a continuation of this two-track pattern in coming months; but there should be no letdown in the top-line growth rate, which will continue to be buffered by formidable AI spending and sustained support from older and wealthier households sitting on sizeable past gains in their financial assets.