The financial markets dodged two potential disrupters this week, as the choice of a new Federal Reserve Chair was revealed and another government shutdown was avoided. President Trump’s chosen nominee for the Fed Chair, Kevin Warsh, is less controversial than some of the other names bandied about and is more likely to be confirmed by the Senate. To what extent the former Fed governor turns out to be a firm advocate of central bank independence from political pressure remains to be seen. But fears that a more pliant choice that would strive to aggressively lower interest rates as the president wants have been calmed, at least for now. That said, it’s important to remember that the Fed chair has only one vote among the 12 voting members of the rate-setting committee, and his main power is as an influencer, not arm-twister. His success, in turn, will depend on how much credibility he earns among his colleagues as an unbiased and effective communicator of sound ideas.

It's unclear how the choice of a less controversial nominee to the chairmanship affects the decision of the current chair to stay on as governor when his role expires in mid-May. Powell has the choice to remain as governor for another two years and there is speculation that, unlike his predecessors, would stay on if he thought the new chair would abandon the core principles of setting policy in accordance with the economy ‘s needs – i.e., pursuing maximum employment and stable inflation – in favor of politically popular goals. With the choice of Warsh, the odds are somewhat higher that he would feel more comfortable leaving the Fed, making the meeting on April 28-29 the last under his leadership and as policymaker. Still, Warsh has more recently been highly critical of the Powell-led Fed, pushing for lower interest rates that some feel was an effort to gain favor with the president.

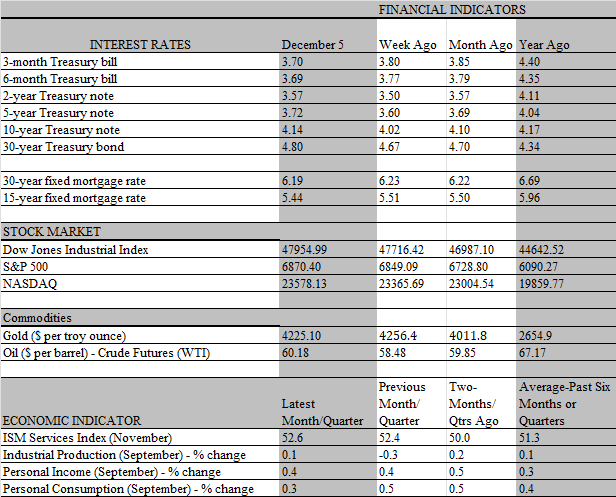

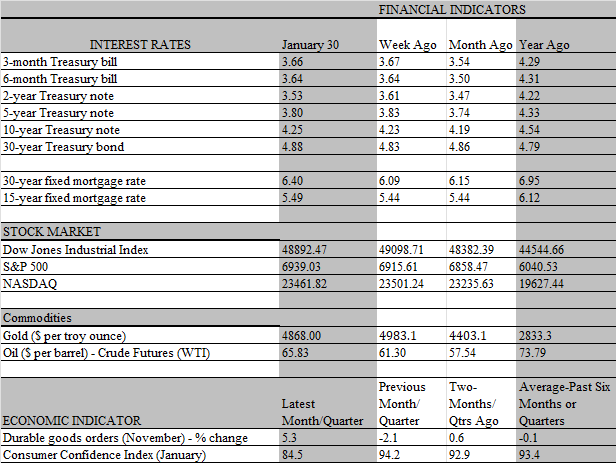

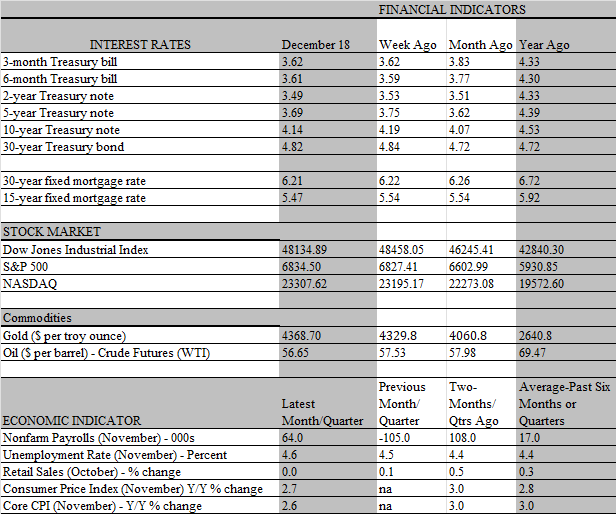

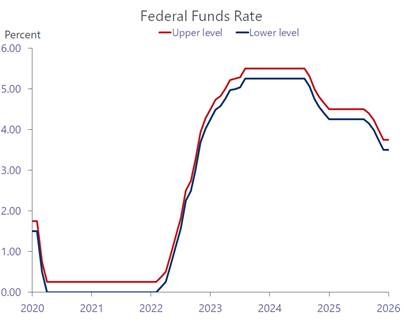

Hence, there are two more meetings with Powell still at the helm -- in March and April – to decide whether the economy needs rates to move lower or higher or remain unchanged. A case can be made for all three options, but for the moment the Fed has decided to move to the sidelines. At this week’s meeting, officials decided to leave rates unchanged, following declines in each of the final three meetings in 2025. The decision came as no surprise as the markets had priced in nearly a 100 percent probability of that outcome. Nor were there any bombshells in Powell’s post-meeting press conference. The presser essentially acknowledged the unfolding of trends in the job market and with inflation, as the risks to both have diminished since late last year, lessening the need for action on the rate front.

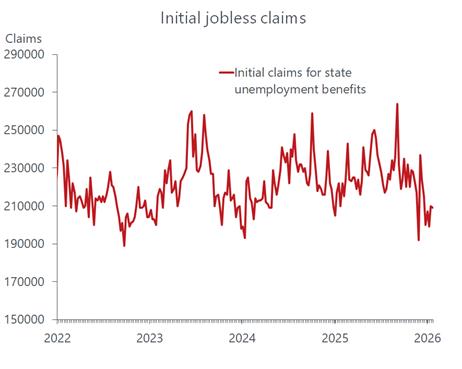

On the labor side, where concerns of deterioration underpinned the rate cuts late last year, the most visible sign that conditions have stabilized is the tick down in the unemployment rate in December from 4.5 percent to 4.4 percent, the first decline in seven months. Companies continue to hold on to workers, as claims for unemployment benefits remain at historically low levels. But not all is smooth sailing for workers and job seekers, as hiring has slumped and unemployed as well as underemployed workers are increasingly being shut out from the workforce or prevented from upgrading their positions. Job security has deteriorated, prompting a big decline in the quite rate, which has fallen well below pre-pandemic levels.

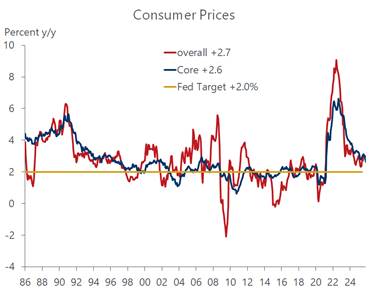

To be sure, heightened job insecurity has not impeded consumer spending, which continues to receive muscular support from older and wealthier households whose net worth has ballooned from years of surging stock prices and home values. Younger and lower-paid households have struggled under the no hiring/no firing environment and the budget-sapping influence of high prices. But even this cohort will be receiving relief in coming months from the formidable tax breaks and refunds poised to hit bank accounts, thanks to last year’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The pending fiscal thrust and the stabilization of labor conditions provide the Fed with a strong incentive to stay on the sidelines for the remainder of Powell’s term. What’s more, inflation remains sticky, hovering closer to 3 percent than the Fed’s 2 percent target, which further weakens the case for cutting rates at this time.

If there is a nagging concern that the Fed may be overstaying its hand it can be found in the mood on Main Street. The disconnect between vibes and hard data continues to be one of the more vexing issues of the day. That discordant note sounded even louder this week, as the Conference Board’s survey of consumer confidence sank to the lowest level in more than a decade in January. Unsurprisingly, discouraging job prospects were the major weight on the Survey’s index, with the percentage of respondents saying jobs were hard to get reaching the highest level since the worst days of the pandemic, in August 2020. As noted, this dispiriting mindset, often labeled a vibecession, has not translated into actual behavior, affirming the notion that people do not always do what they say.

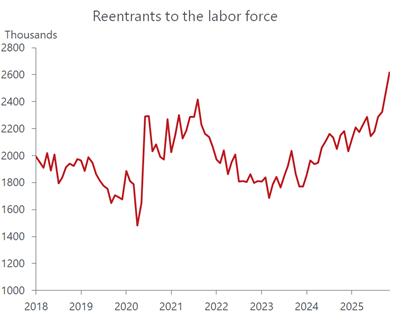

Still, it is a cautionary signal that the spending spigot can run dry when the boost to purchasing power from fiscal stimulus times out. This may well occur after the tax-filing season in the spring and summer, when we believe the Fed will resume its rate-cutting campaign. By then inflation should be mostly liberated from the tariff influence, and without fiscal support households will become more resistant to higher prices. While the ongoing vigor of Ai-related investment and the productivity gains flowing from that spending will sustain an above-trend growth rate in GDP, the productivity gains from that spending will also be a source of labor replacement, underpinning our view that a jobless expansion looms in the foreseeable future.

The prospect of solid top-line growth and moderating inflation would allow the Fed to gradually nudge rates down to a neutral level, echoing the trend seen in the late 1990s. However, the productivity gains of that earlier period did not imperil jobs, as employment rose strongly throughout the period until the excesses from the dot.com boom forced the Fed to hike rates, ending the expansion. This time, signs of AI displacing jobs are already appearing and that trend is likely to continue, reinforcing pressure on the Fed to cut rates later this year.

As it is, the main source of employment growth is coming from labor intensive sectors that are less exposed to improving productivity. Most notable is health and social services, which delivered about 75 percent of all jobs created in the private sector last year. Importantly, health and social services employ a relatively high percentage of foreign-born workers, who are heavily exposed to the immigration crackdown. Should labor shortages become more evident in this sector, the slowdown in job growth already underway would become more acute, weakening the very sector that has become the biggest source of employment.